30 Bayesian Linear Regression*

We learned the basic Bayesian inference in Chapter 22. In this chapter, we apply the Bayesian rule to the linear regression model, and do the Bayesian inference about the unknown regression coefficients. We will also learn how to update our knowledge or do the prediction with the Bayes rule.

We will use several R packages to facilitate Bayesian computation, without the need to worry the mathematical and computational details. Some useful packages for Bayesian modeling and analysis are listed below.

30.1 Bayesian Simple Linear Regression Model

In simple linear regression, we have

We assume or thought the response values are generated from the normal distribution whose mean depends on their corresponding regressor’s value. In Bayesian inference, this normal data model is our likelihood

Here, in SLR, we have three unknown parameters

To be a Bayesian, what do we do next? Bayesians only have one trick. We assign priors to the unknown parameters, then do the posterior inference using Bayes’ rule! The idea is simple, but the big question is HOW. There are countless approaches to construct priors for

The next question is what are

Here

By definition,

Once the prior distributions are specified, with the data likelihood model, the Bayesian simple linear regression model is complete.

Note that in this model, we introduce other parameters, the parameters in the prior distributions,

Example: Capital Bikeshare bayesrules::bikes Data in Washington, D.C.

The data we use for illustration is bayesrules::bikes data set. In particular, we check the relationship between the number of bikeshare rides rides and what the temperature feels like (degrees Fahrenheit) temp_feel.

Rows: 500

Columns: 2

$ rides <int> 654, 1229, 1454, 1518, 1362, 891, 1280, 1220, 1137, 1368, 13…

$ temp_feel <dbl> 64.7, 49.0, 51.1, 52.6, 50.8, 46.6, 45.6, 49.2, 46.4, 45.6, …

30.1.1 Tuning Prior Models

Prior understanding 1:

- On an average temperature day, say 65 or 70 degrees, there are typically around 5000 riders, though this average could be somewhere between 3000 and 7000.

This piece of information gives us an idea of what

We can consider the centered intercept,

Prior understanding 2:

- For every one degree increase in temperature, ridership typically increases by 100 rides, though this average increase could be as low as 20 or as high as 180.

This information tells us about

Graphically speaking, with the centered intercept, we now have the prior regression line, the relationship between rides and temp_feel that we believe it typically has. Note that the prior regression line passes the the centered intercept.

Note that this red line represents just the typical case we believe. There are other (in fact infinitely many) possibilities of

Prior understanding 3:

- At any given temperature, daily ridership will tend to vary with a moderate standard deviation of 1250 rides.

This information is about

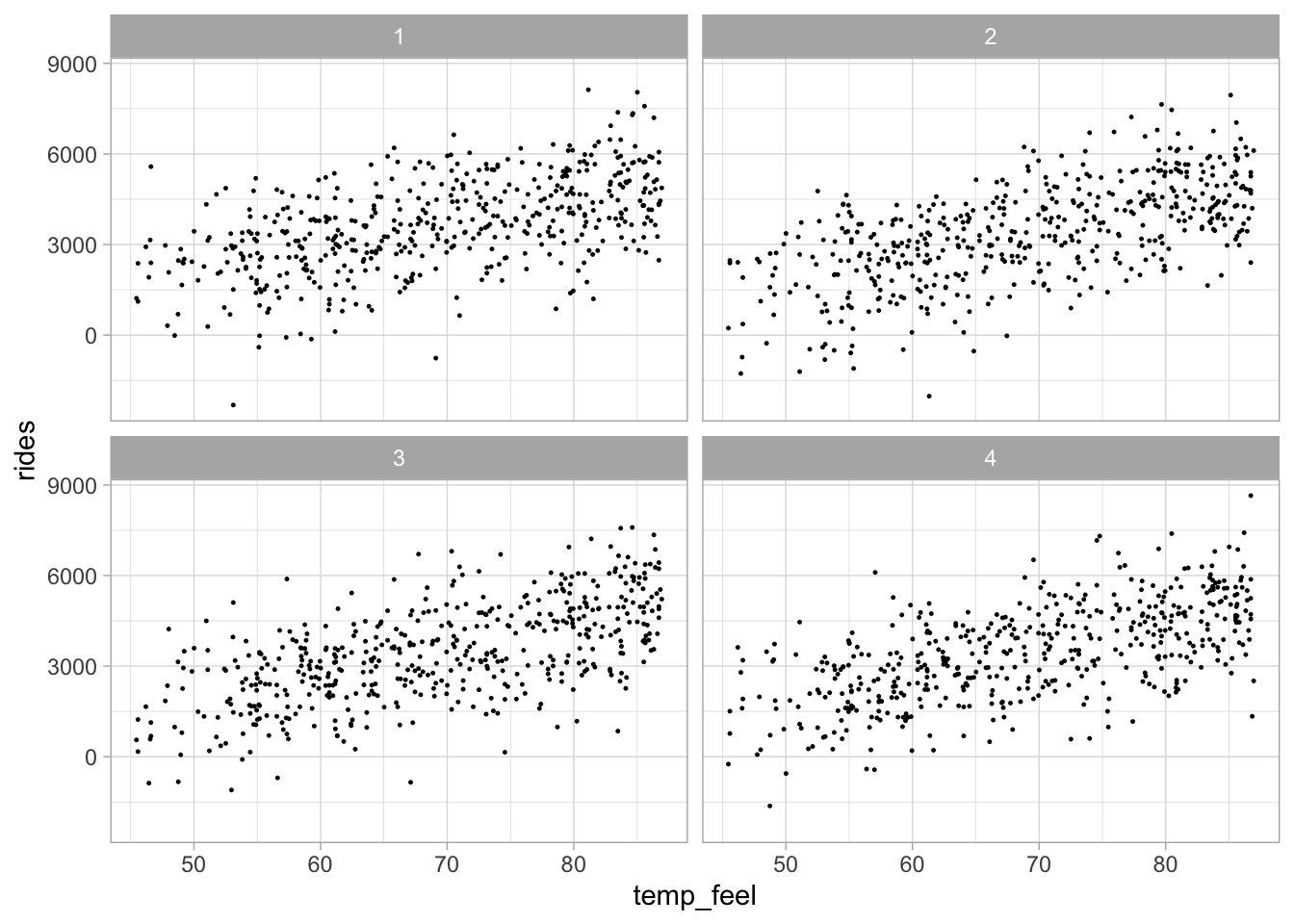

We basically complete the tuning, and all prior distributions are clearly specified. We can generate some prior data points, the data we believe it should look like if we were collecting them, based on the prior model. The following is the simulated prior data when the regression line comes from the prior mean level of

30.2 Posterior Inference

30.2.1 Posterior distribution and sampling

Once the Bayesian model is fully specified, we can start doing posterior inference by obtaining the posterior distribution of unknown parameters. We use Bayes rule to update our prior understanding of the relationship between ridership and temperature using data information provided by likelihood.

The joint posterior distribution is

As you can see,

There are lots of ways to generate/approximate the posterior distribution of parameters. They are discussed in Bayesian statistics course. The method used here is Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). Briefly speaking, MCMC is an algorithm that repeatedly draws the samples of the parameters, and eventually the collection of those draws well represents the posterior distribution of parameters. Again, the details are discussed in a Bayesian analysis course.

Here we use the R rstanarm package that uses RStan syntax1 to do Bayesian inference for applied regression models (arm).

The function helping us draw posterior samples is stan_glm(). The formula is exactly the same as lm(). The family is gaussian because we have a normal data model. prior_intercept is for prior for prior_aux for

bike_model <- rstanarm::stan_glm(rides ~ temp_feel, data = bikes,

family = gaussian(),

prior_intercept = normal(5000, 1000),

prior = normal(100, 40),

prior_aux = exponential(0.0008),

chains = 4, iter = 5000*2, seed = 2024)After tossing out the first half of Markov chain values from the warm-up or burn-in phase, stan_glm() simulation produces four parallel chains of length 5000 for each model parameter:

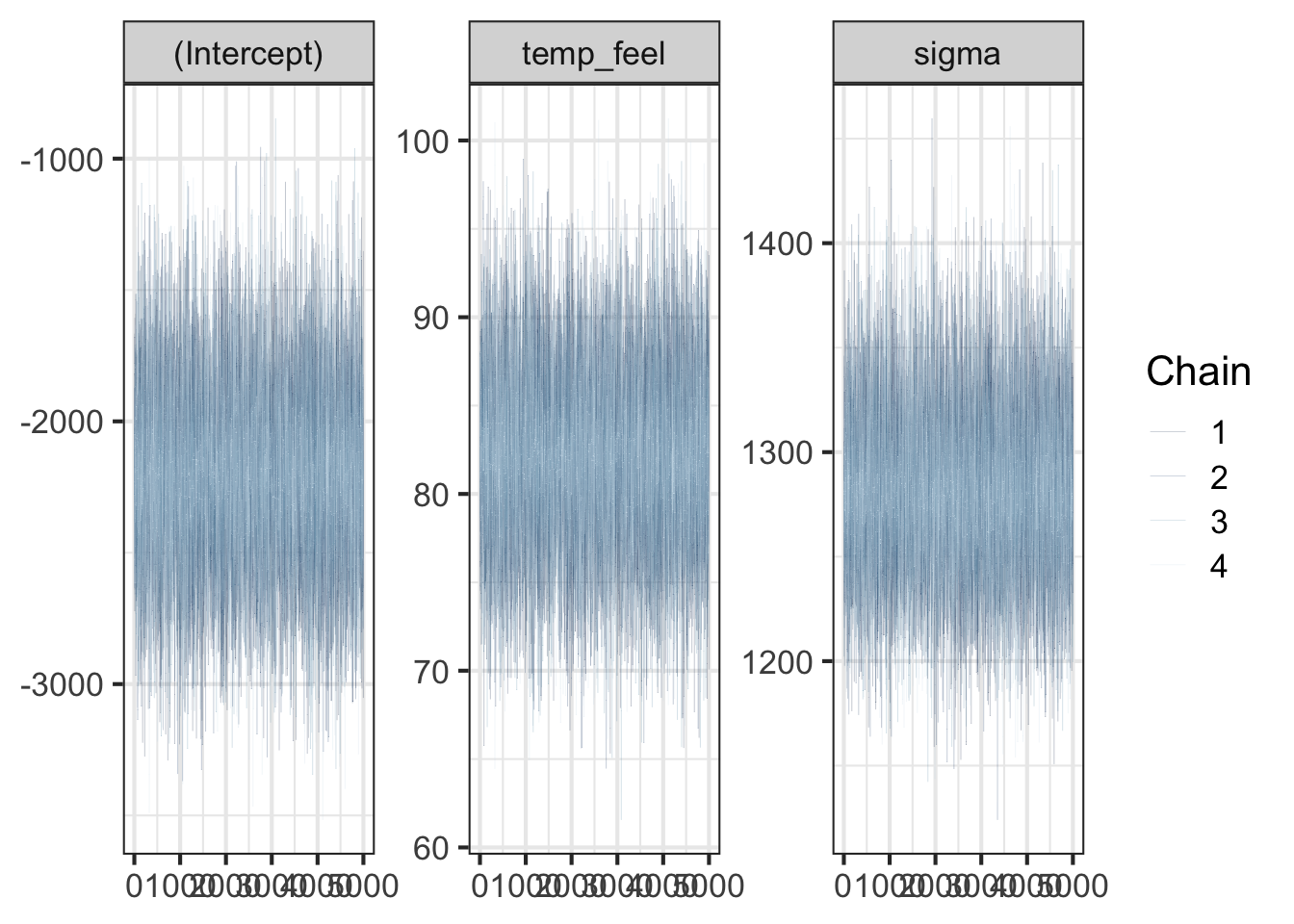

30.2.2 Convergence diagnostics

When we use MCMC to do posterior inference, we need to make sure that the algorithm converges. In other words, the posterior samples drawn by the algorithm should reach a stable distribution, and the distribution basically won’t change much as samples are continuously collected. One way to check the convergence is to check the traceplot, seeing how the sample values move as the iteration goes. If the algorithm reaches the convergence, the traceplots from the 4 independent runs should be mixed and overlapped very well because the 4 set of samples should represent the same posterior distribution. The traceplots obtained from the model fit are mixed well.

# Trace plots of parallel chains

bayesplot::mcmc_trace(bike_model, size = 0.1)

When MCMC just starts, the drawn samples are usually not representative of the posterior distribution. Because of this, we usually don’t include the samples drawn in the early iterations in the final collection of samples used for representing the posterior distribution and for analysis. The following two animations show that it takes a while and several iterations to reach a more stable distribution.

The density curves estimated from the posterior samples approximate posterior distributions. We observe that these four chains produce nearly indistinguishable posterior approximations. This provides evidence that our simulation is stable and sufficiently long – running the chains for more iterations likely wouldn’t produce drastically different or improved posterior approximations.

# Density plots of parallel chains

bayesplot::mcmc_dens_overlay(bike_model)

In addition to visualization, we can use some numeric measures to diagnose convergence. Both effective sample size and R-hat are close to 1, indicating that the chains are stable, mixing quickly, and behaving much like an independent sample.

# Effective sample size ratio

bayesplot::neff_ratio(bike_model)(Intercept) temp_feel sigma

1.023 1.021 0.996 # Rhat

bayesplot::rhat(bike_model)(Intercept) temp_feel sigma

1 1 1 There’s no magic rule for interpreting this ratio, and it should be utilized alongside other diagnostics such as the trace plot. That said, we might be suspicious of a Markov chain for which the effective sample size ratio is less than 0.1, i.e., the effective sample size is less than 10% of the actual sample size. An R-hat ratio greater than 1.05 raises some red flags about the stability of the simulation.

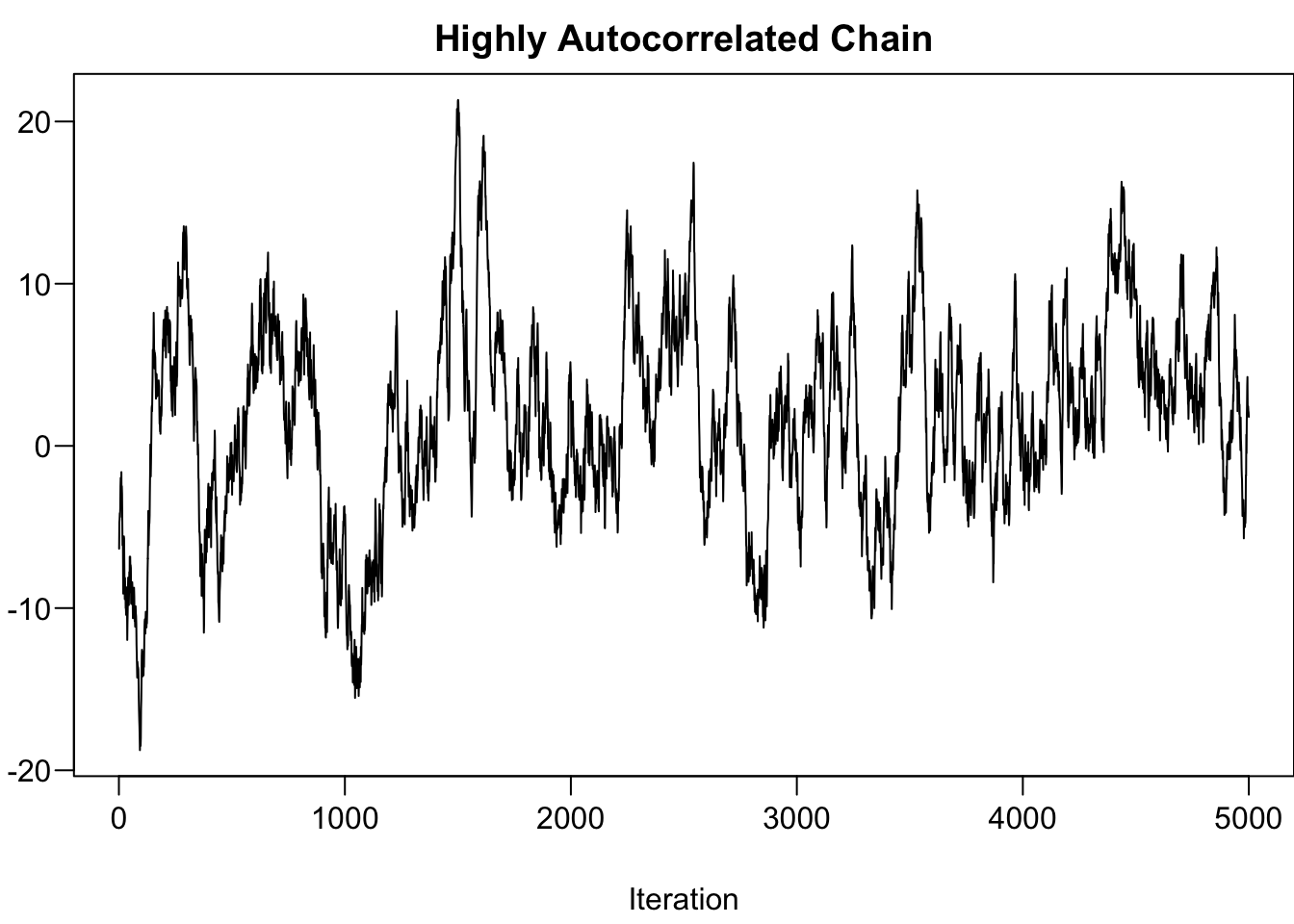

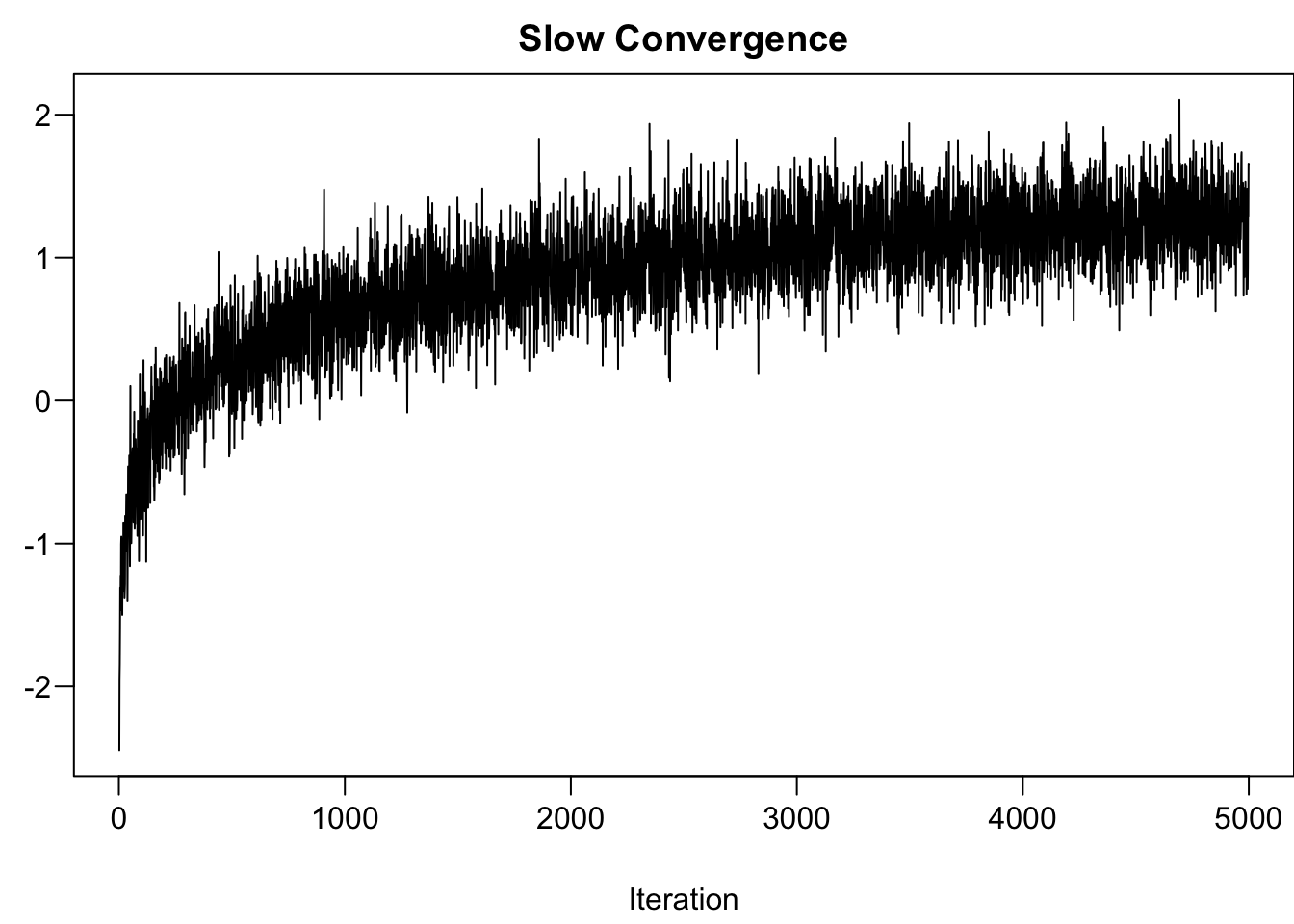

The followings provide two scenarios that MCMC hasn’t reached convergence.

-

Highly Autocorrelated Chain: Effective size is small, not many independent samples that are representative of the true posterior distribution.

- Run longer and thinning the chain

-

Slow Convergence: Need wait longer to have the chain reached a stable mixing zone that are representative of the true posterior distribution.

- Set a longer burn-in or warm-up period

30.2.3 Posterior summary and analysis

Once posterior samples are collected, we can calculate important summary statistics, for example posterior mean, and the 80% credible interval. The two are shown in the first column and the last two columns in the table below.

# Posterior summary statistics

tidy(bike_model, effects = c("fixed", "aux"),

conf.int = TRUE, conf.level = 0.80)# A tibble: 4 × 5

term estimate std.error conf.low conf.high

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -2194. 355. -2648. -1747.

2 temp_feel 82.2 5.08 75.7 88.7

3 sigma 1282. 40.6 1231. 1335.

4 mean_PPD 3485. 80.7 3384. 3591. The posterior relationship (on average) is

The posterior samples are saved in bike_model_df.

# Store the 4 chains for each parameter in 1 data frame

bike_model_df <- as.data.frame(bike_model)

nrow(bike_model_df)[1] 20000head(bike_model_df) (Intercept) temp_feel sigma

1 -1993 77.7 1289

2 -1818 75.9 1292

3 -2003 78.3 1305

4 -2515 87.4 1250

5 -2519 88.0 1293

6 -1666 74.5 1294How do we learn whether or not

Instead of making a dichotomous judgement, in the Bayesian world, we provide the probability of something happening. Anything is not just black or white. We live in a world full of different gray, a continuum showing the degree of our credence. In our example, the probability that

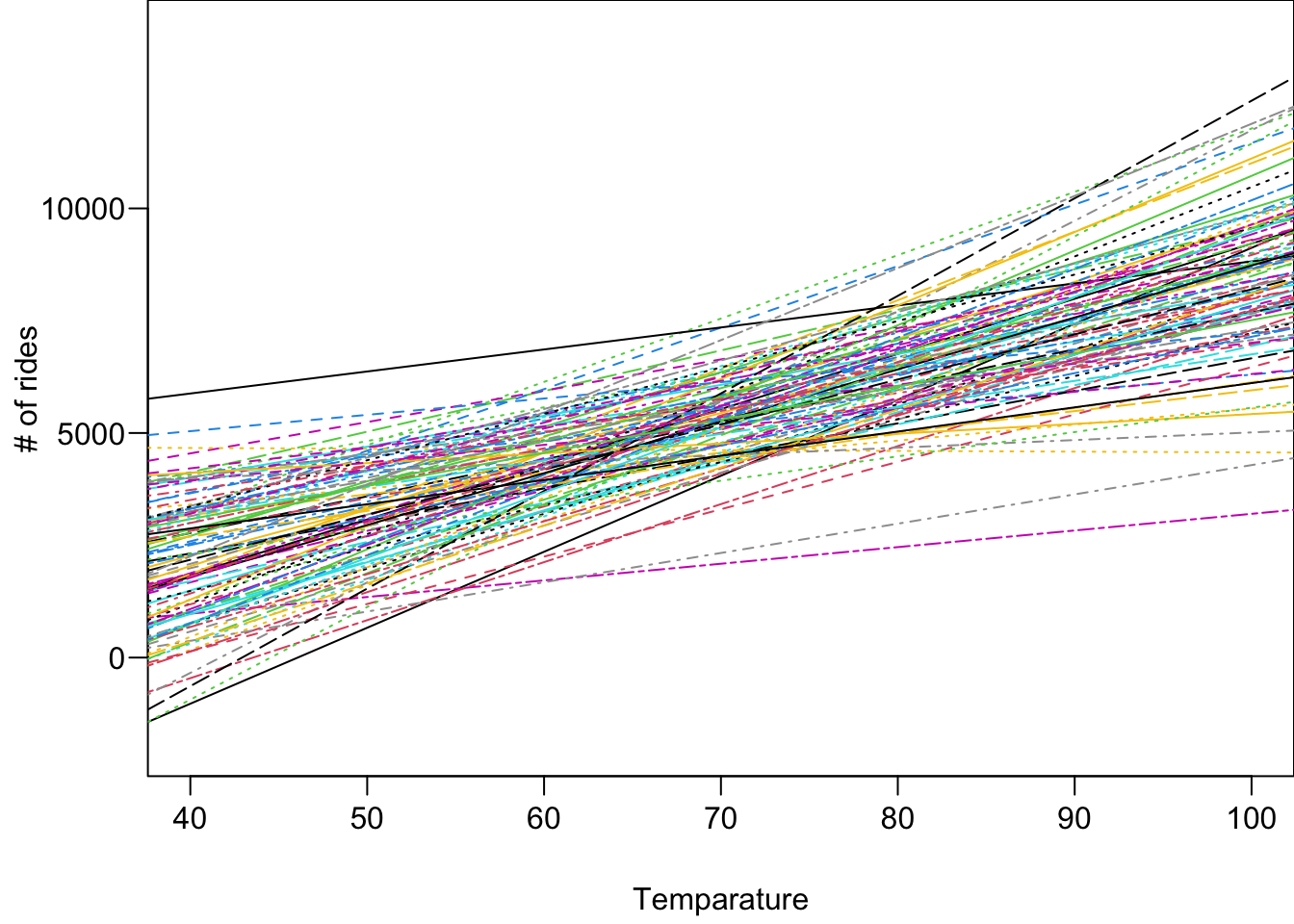

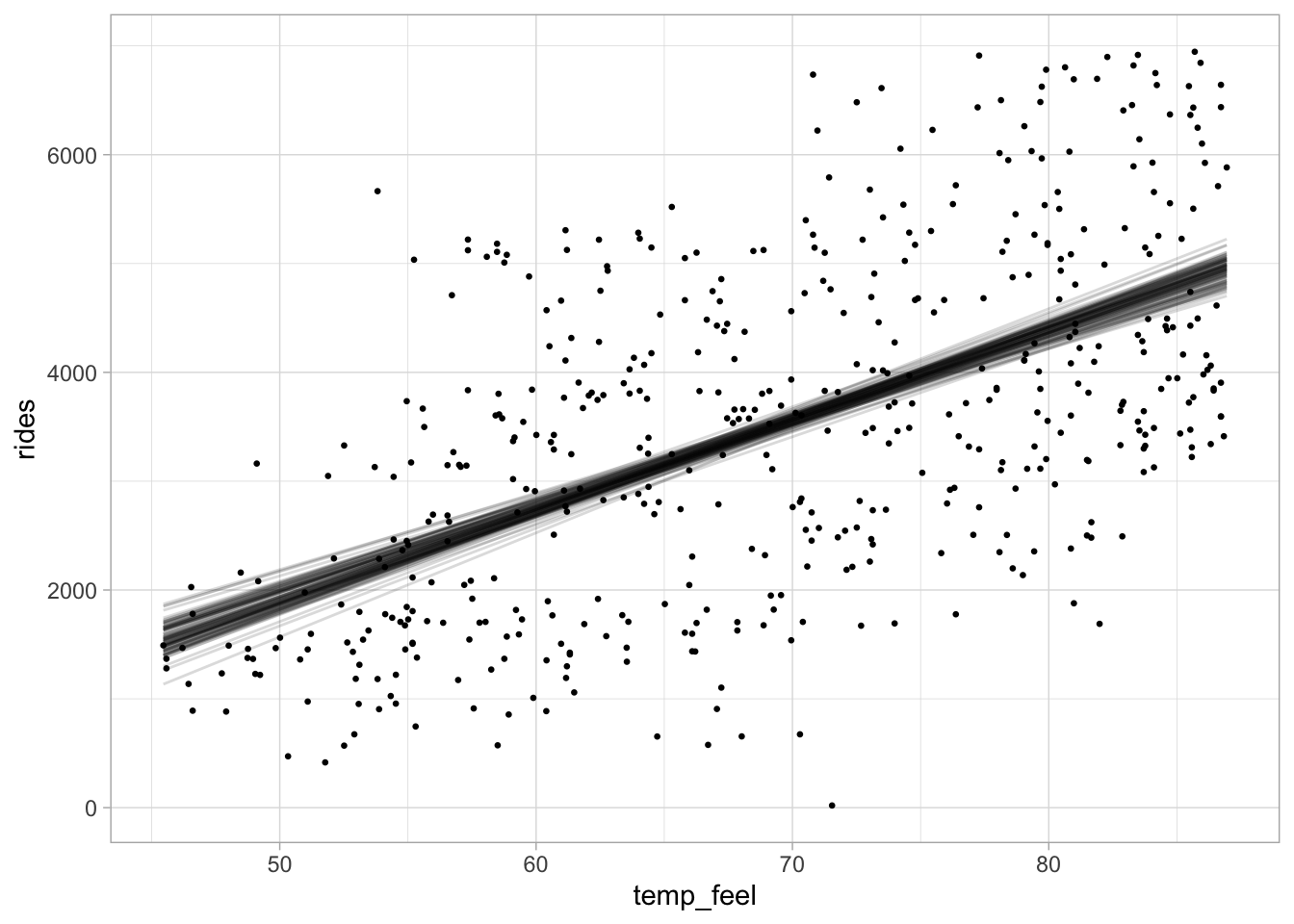

The figure below shows 100 posterior regression lines, one corresponding to one pair of

For each posterior draw

We then can have 20000 different posterior predictive response distributions, and 20000 different posterior predictive response data sets. Those data are what we think the data will look like if the true data generating mechanism is one of the regression model with parameters